북한의 수확이 부실하면 1990년대 수백만 명의 시민을 죽게 한 파괴적인 기근이 반복될 위험에 직면할 수 있다.

소식통들은 북한이 기후변화로 인한 황폐한 여름 홍수와 환경 위협에 대응하기 위한 국가의 노력 부족으로 인해 복합적인 영향, 식량 수입의 1위 원천을 차단하는 중국과의 무역 금지, 생산 유인을 파괴하는 구시대 집단주의 농업 시스템 등 여러 요인으로 인해 또 다른 재앙의 위기에 처했다고 말했다.

더욱이, 핵무기를 추구하는 국가의 경우 11월 1일 북한과 무역을 재개한 전통적인 동맹국인 중국 및 러시아 이외의 국가의 상당한 식량 원조에 크게 부적격하게 될 가능성이 높다.

이는 수년간 진행된 위기이며 평양의 비밀스러운 정부는 수개월째 시민들에게 곤경에 처할 것을 경고하고 있다.

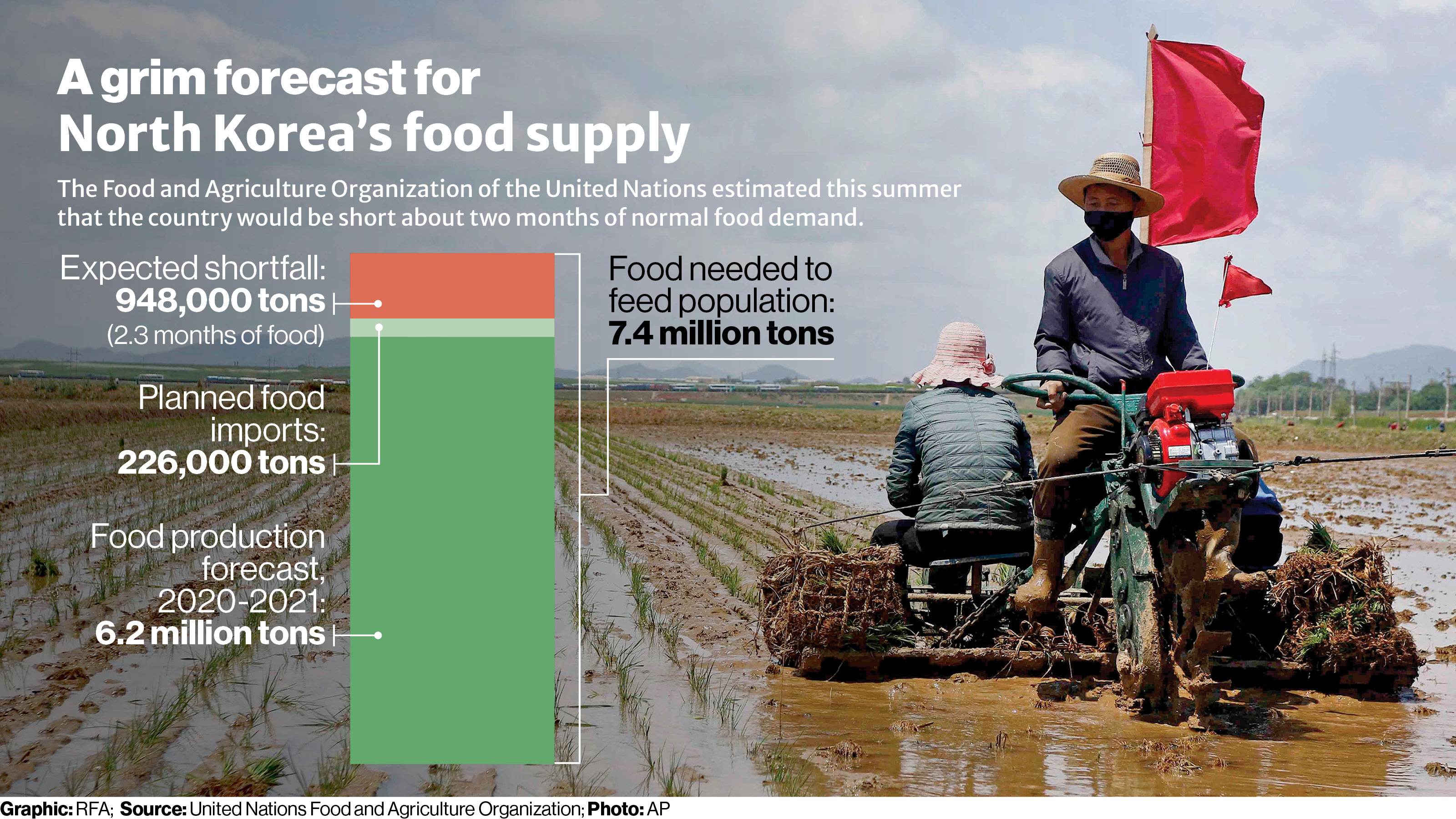

유엔 식량농업기구는 지난 6월 북한이 올해 약 86만t의 식량 부족을 겪을 것으로 전망했는데, 이는 약 2개월 만에 2천500만 명의 인구가 소비하는 양이다.

세계식량계획(WFP)의 추정에 따르면 그 인구의 40%가 영양실조에 걸렸고 올해 이미 기아 사망자가 보고된 상황에서 가을 수확은 차질 없이 진행되어야 했다.

크레딧: 로이터

북동부 함경북도의 한 집단농민은 오사카에 본사를 둔 북한 뉴스 서비스 아시아 프레스에 "올해 농사가 좋지 않았다"고 밝혔고, 이 회사는 RFA의 요청으로 소스에 연락했다.

이 농부는 국경을 넘어 불법 밀반출된 중국 휴대전화를 통해 보낸 문자메시지를 통해 일본 매체에 "올해 농산물 수확량이 작년보다 나빠 농민들이 제대로 된 배급량을 받을 수 없을 것"이라고 말했다.

수확이 저조하다는 소식은 탈출해 현재 남한에 거주하고 있는 탈북민들에게 전해졌으며, 이들 중 상당수는 여전히 북한에 있는 가족과 접촉을 유지하고 있다.

지난해 도피하기 전까지 북한 국경 인근 도시 외곽에 살던 한영선이라는 가명으로 알려진 난민은 RFA 한국서비스에 "작년과 비교하면 어떻게 되는지 모르겠지만 비료가 없어서 그런 것 같다. 비료 없이는 농사를 지을 수 없다"고 말했다.

수입 비료가 부족한 것은 2020년 초 코로나19 대유행 초기 평양과 베이징이 국경을 폐쇄하고 모든 무역을 중단하기로 한 결과다.

이 조치로 북한 경제가 황폐화되고 식량 가격이 폭등했으며, 중국으로부터의 수입 없이는 국내 식량 생산과 수요 사이의 격차를 줄일 수 없었다.

지난 10월 중순 당국은 최소한 2025년까지 식량난 문제가 지속될 수 있다고 시민들에게 경고했는데, 북한 주민들은 1994∼1998년 기근 때보다 부족이 더 심각할 수 있다고 경고한 바 있다.

크레딧: 로이터

그러나 정부가 시민들에게 가능한 한 많이 절약할 것을 경고함에 따라 지도자들은 여전히 국가의 군인을 최대한 적절하게 먹일 수 있도록 하겠다고 약속하고 있다.

이 농부는 아시아 프레스와의 인터뷰에서 "군을 위해 따로 둔 쌀이 최우선이기 때문에 농가에서 나오는 배급량이 한두 달 정도 부족할 것이라고 말하고 있다"고 말했다.

안보상의 이유로 익명을 요구한 함경북도 주민은 RFA에 "대부분의 해에 군은 수확량의 60%, 농민들은 40%를 얻는다"고 말했다.

그러나 올해는 군대가 필요한 것을 가져갈 것입니다. 작물 수확량이 적기 때문에 군인들은 말 그대로 농부 몫을 먹을 것입니다.

김정은은 '얇은 얼음 위를 걷는 것'이라고 느낄 정도로 군의 먹이를 유지하는 것이 체제 생존에 매우 중요하다고 한국 국가정보원이 10월 말 보도했다.

이를 위해 당국은 밀수입을 막기 위해 집단 농장에 대한 감시를 강화했다. 아시아 프레스 소식통은 올해 농부들이 다른 해처럼 공식 식량 공급원을 보충하기 위해 사용하는 사설 정원을 숨길 수 없다고 말했다.

아시아프레스 이시마루 지로 수석은 "농민의 입장에서 보면 농장에서 일해서 생계를 유지하기 어려워 여분의 먹거리를 위해 산 속 작은 땅에서 사적으로 농사를 짓고 있다"고 말했다.

그는 "우리 소식통들은 모두 농작물 계산에 포함되었다고 말했다.

RFA는 최근 수확 기간 동안 무료 농장 노동을 위해 동원된 시민들이 의복에 쌀 알갱이를 숨기지 않도록 경비원으로부터 무작정 징발을 당했다고 보고했다.

북한의 수확량에 대한 공식 통계는 아직 나오지 않았지만 수확한 쌀을 완전히 건조시켜 탈곡하면 수주가 걸릴 수 있는 과정이 될 것으로 예상된다.

기후, 코로나바이러스 공유 비난

북한 정부는 현재의 식량 위기를 팬데믹, 핵무기 프로그램을 질식시키기 위한 미국과 유엔의 제재, 악천후 등 많은 외부 요인으로 돌렸다.

팬데믹이 시작된 지 두 여름 동안 폭우로 인한 심각한 홍수와 일련의 태풍으로 인해 전국 여러 지역의 농장과 농작물이 파괴되었습니다.

기후변화가 이례적으로 습한 여름을 초래한 원인으로 여겨지지만, 북한의 환경보호 미흡이 홍수 피해를 가중시켰다고 한국 경희대 교수는 RFA에 말했다.

콩우석은 1990년대 중반의 고난의 행군부터 사람들이 먹이를 구하기 위해 산에 가서 장작을 조달하고 산에 테라스 밭을 짓고, 외화를 벌기 위해 목재를 해외로 수출해 왔다"고 1990년대 중반의 기근을 한국어로 표현했다.

그는 "기상 현상으로 인한 피해는 산림이 파괴되는 것과 일치했다"고 말했다.

한편, 코로나19 방역 차원에서 부과된 중국과의 무역금지 조치로 북한은 식량 공급의 주요한 원천을 찾지 못했고, 양국은 11월 1일 철도 화물 운행을 재개했지만, 거의 2년여의 모라토리엄이 시행된 데는 큰 타격을 입었다.

권태진 한국 GS&J 북한·동북아연구센터장은 RFA에 "북한은 자국 생산을 바탕으로 항상 식량 부족이 있어 식량을 수입해야 한다. 무역을 기반으로 수요를 충족시킬 수 없다면 인도주의적 지원이 필요하다"고 말했다.

권 위원장은 북한이 지난 1월부터 8월까지 4천t의 곡물을 수입했는데, 이는 전염병이 국경을 폐쇄하기 몇 달 전까지 포함된 지난해 같은 기간 수입한 11만t의 일부에 불과하다고 지적했다.

중국과 북한의 무역이 재개되기 전 인터뷰를 받은 권 대표는 "가능한 만큼의 식량을 수입하더라도 내년에는 여전히 식량 부족이 있을 것"이라며 "국제사회에 인도적 지원을 요청해야 할 것"이라고 말했다.

조지타운대 윌리엄 브라운은 RFA에 "국제사회가 북한의 핵 야망을 경계하고 있어 평양에 더 많은 식량 원조를 제공하는 데 열을 올리지 않고 있다"고 말했다.

브라운 대변인은 "4~5년 전까지만 해도 세계식량계획, 유엔 기구 등으로부터 꾸준히 식량 원조를 받았지만, 제재가 발효된 이후 최근 몇 년 동안 중국과 러시아의 일부 식량 원조를 제외하고는 실제로 거의 받지 못했다"고 말했다.

크레딧: 로이터

인센티브가 없습니다.

브라운은 북한의 식량 체계가 갖는 가장 큰 문제는 집단 농업 체계에 의존하고 있다는 것이다.

브라운은 "농사는 매우 힘든 일이고 위험부담도 많다. 날씨가 어떨지 모른다. 그래서 위험부담에 대한 보상을 받아야 한다. 열심히 노력한 것에 대한 보상을 받아야 한다. 북한 집단은 보상을 하지 않는다"고 말했다.

일본 주간지 '슈칸 키뇨비'의 문송 후이 수석 편집장은 RFA에 "북한 정부는 더 많은 대중을 동원해 무료 농작물 노동을 하지만 이 관행은 농업 생산을 돕는 것보다 오히려 해를 끼친다"고 말했다.

문씨는 "쌀을 짓는 것은 쉽지 않고 오랜 시간 동안 이 경험을 쌓아야 하는데, 쌀을 짓는 경험이 없는 이 동원된 학생들이 밖으로 내보내져 제대로 하고 있지 않다"고 말했다.

그는 "북한의 한 농민에게 실제 농민들이 다시 고쳐야 한다는 말을 들었는데, 더 큰 부담을 주고, 이 동원된 노동자들이 멀리서 농장에 오면 농민들이 식사와 숙소를 제공해야 한다"며 "농민들에게 큰 부담이 된다"고 말했다.

RFA 한국서비스는 노종민, RFA 한국서비스는 천소람, 박수영, RFA 영문서비스는 나와르네메가 보고하고. 클레어 리, 이진 주니의 번역. 유진 의 영어로 쓴다.

Another bad harvest in hungry North Korea underscores root cause of food crisis

A poor harvest in North Korea may raise the risks that the country will face a repeat of the devastating famine it suffered in the 1990s that left millions of citizens dead.

Sources said a number of factors have left North Korea on the brink of another disaster: devastating summer floods from climate change, compounded by a lack of effort in the country to meet the environmental threat; a trade ban with China that shut off its number one source of food imports; and an antiquated collectivist agricultural system that destroys incentives to produce.

Moreover, the country’s pursuit of nuclear weapons is likely to leave it largely ineligible for significant food aid from countries outside of traditional allies China, which resumed trade with North Korea on Nov. 1, and Russia.

This is a crisis that has been years in the making, and the normally secretive government in Pyongyang has been warning its citizens of troubles for months.

The U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization projected in June that North Korea would be short about 860,000 tons of food this year, or the amount that the population of 25 million consumes in about two months.

With 40 percent of that population undernourished, according to World Food Program estimates, and with starvation deaths already reported this year, the autumn harvest had to go off without a hitch. It did not.

Credit: Reuters

“Farming was not good this year” a collective farmer from the country’s northeastern province of North Hamgyong told the Osaka-based North Korea news service Asia Press, which contacted their source at RFA’s request.

“This year’s farming yields are worse than last year’s, so the farmers won’t be able to receive their proper rations,” the farmer told the Japanese outlet over text messages sent via a Chinese mobile phone illegally smuggled across the border.

News of the poor harvest has reached North Korean refugees who escaped and are now living in South Korea, many of whom still maintain contact with their families in the North.

“I don’t know how it is compared to last year, but I think it’s because they had no fertilizer. You can’t really farm without fertilizer,” a refugee identified by the pseudonym Han Young-sun, who lived on the outskirts of a city near the North Korean border until escaping last year, told RFA’s Korean Service.

The lack of imported fertilizer is the result of the decision by Pyongyang and Beijing to shut down their border and suspend all trade at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020.

The move devastated the North Korean economy and caused food prices to skyrocket. Without imports from China, the gap between domestic food production and demand couldn’t be closed.

In mid-October, authorities told citizens food scarcity problems could last through at least 2025. North Koreans previously had been warned shortages could be worse than during the 1994-1998 famine that killed, according to some estimates, as much as 10 percent of the population.

Credit: Reuters

But as the government warns its citizens to conserve as much as they can, leaders are still promising to keep the nation’s soldiers as adequately fed as possible.

“They are saying that the rations from the farms are going to be short by about a month or two because the rice put aside for the military is the main priority,” the farmer told Asia Press.

In most years, the military would get 60 percent of the harvest and the farmers 40 percent, a resident from North Hamgyong province who requested anonymity for security reasons told RFA.

But this year the army will take whatever it needs. Given the low crop yields, the soldiers will likely literally eat into the farmers’ share.

Keeping the military fed is so important to regime survival that Kim Jong Un has said he feels like he is “walking on thin ice,” South Korea’s National Intelligence Service reported in late October.

To that end, authorities have bolstered surveillance of collective farms to prevent smuggling. Asia Press’ source said that farmers this year were unable to hide private gardens they use to supplement their official food sources, as they have in other years.

“From the farmer’s point of view, it’s hard to make a living by working on the farm, so they have been privately farming on small land in the mountains for extra food,” said Jiro Ishimaru, Asia Press’ chief editor.

“Our sources said that all of them were included in the farm crop calculation,” he said.

RFA reported recently that citizens mobilized for free farm labor during the harvest were subject to being frisked by guards to ensure they were not hiding grains of rice in their clothing.

Official statistics on the North Korean harvest have not yet been released, but figures are expected once the harvested rice is completely dried a threshed, a process that can take weeks.

Climate, coronavirus share blame

The North Korean government has blamed the current food crisis on many outside factors—the pandemic, U.S. and U.N. sanctions aimed at choking off its nuclear weapons program, and bad weather.

In the two summers since the pandemic began, severe flooding from heavy rains and a series of typhoons destroyed farms and crops in many parts of country.

Climate change is seen as the cause for the unusually wet summers. But a professor at South Korea’s Kyung Hee University told RFA that North Korea’s lack of environmental protection compounded the damage from the flooding. For years, North Korea’s landscape has been stripped of vegetation that would have held up some of the water.

“Starting from the Arduous March in the mid-1990s, people have gone to the mountains to find food, procure firewood, build terrace fields in the mountains, and export timber overseas to earn foreign currency,” said Kong Woo Seok, using the Korean term for the mid-1990s famine.

“Damage from meteorological phenomena coincided with the forests being destroyed,” he said.

Meanwhile, the trade ban with China imposed as a protection against the coronavirus left North Korea without a significant source of its food. The two countries resumed rail freight on Nov. 1, but the almost two years that the moratorium has been in place have taken a toll.

“North Korea is always short of food based on its own production, so it must import food. Humanitarian aid is needed if they cannot meet demands based on trade. But they are not procuring adequate imports or assistance this year,” Kwon Tae Jin, director for the Center for North Korea & Northeast Asian Studies at GS&J in South Korea, told RFA.

Kwon noted that from January to August, North Korea imported 4,000 tons of grain, a mere fraction of the 110,000 tons it imported during the same period last year, which included some months before the pandemic shut the border.

“Even if they import as much food as they can, they will still be short on food next year. They will have to ask the international community for humanitarian assistance,” said Kwon, who was interviewed before trade between China and North Korea resumed.

The international community is, however, wary of North Korea’s nuclear ambitions and therefore unenthusiastic about providing Pyongyang with more food aid, Georgetown University’s William Brown told RFA.

“Until about four or five years ago, they steadily received food aid from the World Food Program, UN agencies and elsewhere, but in recent years since the sanctions came into effect, they have actually received very little food aid [except] some from China and Russia," Brown said.

Credit: Reuters

No incentives

Brown said the overarching problem with North Korea’s food system is that it relies on a collective farming system.

“Farming is very difficult work and there's a lot of risk-taking. You don't know what's the weather is going to be like. So, you need to be rewarded for risk-taking. And you need to be rewarded for working hard. And the North Korean collectives don't reward," Brown said.

North Korea’s government mobilizes the broader public for free farm labor, but the practice hurts agriculture production rather than helping it, Mun Song Hui, chief editor of the Japan-based weekly magazine Shukan Kinyobi, told RFA.

“It is not easy to farm rice and you have to gain this experience over a long time, right? However, these mobilized students, who have no experience farming rice, are put out there and are not doing it correctly,” said Mun.

“I have heard from a North Korean farmer that the actual farmers have to fix it again and it puts more pressure on them. Also, if these mobilized workers come to the farms from far away, the farmers have to provide the meals and lodging for them. It becomes a large burden for the farmers,” she said.

Reported by Jong Min Noh, Soram Cheon and Sooyoung Park for RFA’s Korean Service and Nawar Nemeh for RFA’s English Service. Translated by Claire Lee and Leejin Jun. Written in English by Eugene Whong.

굶주린 북한의 또 다른 나쁜 수확은 식량 위기의 근본 원인을 강조한다